Throughout his life the English physician-philosopher Sir Thomas Browne (1605-82) possessed an insatiable curiosity upon myriad subjects. Books upon ancient history, geography, philosophy, anatomy, theology, cartography, embryology, medicine, cosmography, ornithology, mineralogy, zoology, travel, law, mathematics, geometry, literature, both Continental and English, the latest advances in scientific thinking in astronomy and chemistry, as well as books on astrology, alchemy and the kabbalah, are all listed in the 1711 sales auction catalogue of his library. Browne was often attracted to subjects considered exotic, mysterious, or little-known. It should come as no surprise therefore that the distant land of China should attract the interest of the learned doctor.

During Browne’s life-time a slow but gradual increase in trade and import of Chinese goods to Europe occurred. Ceramic earthenware was among the earliest and most popular of all Chinese imports, to such an extent that it's very name became synonymous to the country of its origin. However, the manufacture of Chinese porcelain remained unknown in the West. Browne in his vanguard work of the English scientific revolution, Pseudodoxia Epidemica (1646) determined to resolve this mystery. Though quoting Portuguese travellers to China, Browne's observations upon Chinese porcelain are the earliest extant in English.

We are not thoroughly resolved concerning Porcellane or China dishes, that according to common belief they are made of Earth, which lieth in preparation about an hundred years under ground;.........Gonzales de Mendoza, a man imployed into China from Philip the second King of Spain, upon enquiry and ocular experience......found they were made of a Chalky Earth; which beaten and steeped in water, affordeth a cream or fatness on the top, and a gross subsidence at the bottom; out of the cream of superfluitance, the finest dishes, saith he.....

Later confirmation may be had from Alvarez the Jesuit, who lived long in those parts, in his relations of China.The latest account hereof may be found in the voyage of the Dutch Embassadors sent from Batavia unto the Emperour of China, printed in French 1665 which plainly informeth, that the Earth whereof Porcellane dishes are made, is brought from the Mountains of Hoang, and being formed into square loaves, is brought by water, and marked with the Emperour's Seal: that the Earth itself is very lean, fine, and shining like Sand: and that it is prepared and fashioned after the same manner which the Italians observe in the fine Earthen Vessels of Faventia or Fuenca.. they are so reserved concerning that Artifice, that 'tis only revealed from Father unto Son. [1]

Elsewhere in Pseudodoxia Epidemica Browne demonstrates his awareness of China’s vast population, stating -

So the City of Rome is magnified by the Latins to be the greatest of the earth; but time and Geography inform us, that Cairo is bigger, and Quinsay in China far exceedeth both.[2]

Athanasius Kircher (1601-80) a near contemporary and favourite author of Browne's, was a priest who had various missionary contacts to China through the Jesuit Order. Like the Norwich doctor, Kircher had an insatiable curiosity and fascination with obscure or esoteric learning, named in the introduction to his Oedipus Aegypticus (1656) as - ‘Egyptian wisdom, Phoenician theology, Hebrew kabbalah, Persian magic, Pythagorean mathematics, Greek theosophy, Mythology, Arabian alchemy, Latin philology’. [3]

When Athanasius Kircher published his China illustrata in 1667 Browne was finally able to satisfy his curiosity about the land of the mysterious and distant East. Kircher’s China illustrata [4] was a work of encyclopedic breadth and the most informative book available on China for many years. It included accurate maps as well as mythical creatures, and drew heavily on reports by the Jesuits Michael Boym and Martino Martini who worked in China. Kircher emphasized the Christian elements of Chinese history, both real and imagined and highlighted the early presence of Nestorian Christians in China. However, he also claimed the Chinese were descended from the sons of Biblical Ham and that Chinese characters originated from Egyptian hieroglyphs ! In the above illustration Chinese botany and horticulture, costume and customs, along with architecture, are each faithfully recorded from an eyewitness account of a social gathering, feasting upon the giant 'polomie' jackfruit.

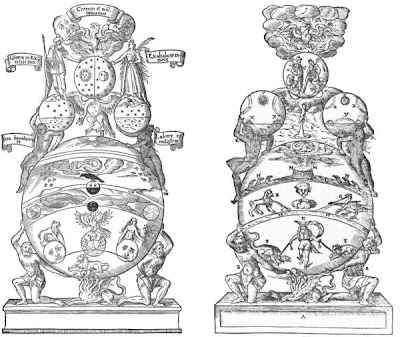

Kircher’s at times wildly misguided theories in comparative religion are described by Joscelyn Godwin for the illustration below as - ‘A confused memory of Buddhist iconography may have led to this weird image, which Kircher regards as the equivalent of the Great Mother of Western religions. To the Egyptians she is Isis, the the Greeks Cybele. The lotus upon which she is seated represents the ‘Humid principle' which nourishes all things’. [5]

Sir Thomas Browne retained a fascination with China until late in his life. His extraordinary, and at times surreal, list of books, pictures and objects rumoured to exist, lost, or imagined, Bibliotheca Abscondita (circa 1675) includes the 'wish-list' entry of - The Works of Confucius the famous Philosopher of China, translated into Spanish. [6]

Inspired by the popularity of the cryptic verse of Nostradamus which were first translated into English in the 1670's, Browne’s A Prophecy concerning the future State of Several Nations (circa 1675) predicts the end of the Slave-trade, a full one and a half centuries before its eventual abolition-

When Africa shall no longer sell out its Blacks

to be slave and Drudges in the American Tracts

Browne continues with the 'prophecy' of -

When Batavia the Old shall be contemn’d by the New,

and a new Drove of Tartars shall China subdue.

- with the following explanation -

Which is no strange thing if we consult the Histories of China, and successive Inundations made by Tartarian Nations.... And this hath happened from time beyond our Histories: for, according to their account, the famous Wall of China, built against the irruptions of the Tartars, was begun above a hundred years before the Incarnation.

Browne also speculated upon a quicker trading route to Cathay (China’s ancient name) for European traders via circumnavigating the Arctic Circle -

When Nova Zembla shall be no stay

Unto those who pass to or from Cathay.

- once more accompanied by explanation.

That is, Whenever that often sought for Northeast passage unto China and Japan shall be discovered, the hindrance whereof was imputed to Nova Zembla; ......the main Sea doth not freeze upon the North of Zembla except near unto Shores; so that if the Moscovites were skilfull Navigatours they might, with less difficulties, discover this passage unto China: but however the English, Dutch and Danes are now like to attempt it again. [7]

Finally, its a neat coincidence that Norwich, the city where Sir Thomas Browne lived for the greater part of his life, has a cultural heritage which is associated with the archetypal mythic creature of China. Ever since the days of the Medieval Guilds Norwich civic processions have been led in parade by the half playful, half fearsome creature 'Snap’ the Dragon; Browne in his day may have witnessed this civic event and the Dragon, emblematic of China, continues to this day to be celebrated as part of Norwich’s cultural heritage.

Part 2

Time hath endless rarities, and shows of all varieties; which reveals old things in heaven, makes new discoveries in earth, and even earth it self a discovery. -Urn-Burial

With their highly polarized themes, imagery and prose style, Browne’s two philosophical discourses Urn-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus of 1658 may be interpreted as being compatible with concepts originating from classical Chinese philosophy. However, in order to fully apprehend this connection, its useful to first consult the foremost scholar of comparative religion and esoteric learning, the seminal psychologist, Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961).

In 1929 Jung received a copy of the Chinese Taoist text The Secret of the Golden Flower from the Sinologist and Missionary Richard Wilhelm who discusses the possibility that his translated text - a blend of Buddhism and 'inner elixir' Taoism, may have originated in the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) at the beginning of Nestorian Christianity. For Jung, Wilhelm's translated text proved to be revelatory. In his 1931 commentary to The Secret of the Golden Flower Jung reminded his reader that-

Science is the tool of the Western mind...it is part and parcel of our knowledge and obscures our insight only when it holds that the understanding given by it is the only kind there is. The East has taught us another, wider, more profound, and higher understanding, that is understanding through life. [8]

Writing before the establishment of the People's Republic in 1949, Jung stated -

'Western consciousness is by no means the only kind of consciousness there is; it is historically conditioned and geographically limited, and representative of only one part of mankind. The widening of our consciousness ought not to proceed at the expense of other kinds of consciousness; .... The European invasion of the East was an act of violence on a grand scale, and has left us with the duty - noblesse oblige (privilege entails responsibility) - of understanding the mind of the East. This is perhaps more necessary than we realize at present.' [9]

The word Tao itself Jung noted, has no satisfactory translation and is variously translated as ‘The Way’ ‘Meaning’ or even ‘God’. Jung comments-

'The undiscovered vein within us is a living part of the psyche; classical Chinese philosophy names this interior way "Tao”, and likens it to a flow of water that moves irresistibly towards its goal. To rest in Tao means fulfillment, wholeness, one’s destination reached; the beginning, end, and perfect realization of the meaning of existence innate in all things. Personality is Tao.'[10]

The Taoist text The Secret of the Golden Flower confirmed Jung's hypothesis - that the substratum of the human psyche has no fundamental differentiation. Within both Western and Eastern psyche, Jung detected, are deeply embedded symbols drawn from a shared collective unconscious. The concepts of medieval western alchemy, just like Chinese Taoist philosophy, utilize similar symbols which describe psychological processes entirely independent of cultural references or contact with other sources.

Classical Chinese philosophy in Jung’s view was the natural counterpart to medieval alchemy, stating-

the alchemical mysterium coniunctionis is the Western equivalent of the fundamental principle of classical Chinese philosophy, namely the union of yang and yin in Tao.[11]

Polarity and the union of the opposites is central to Taoist thought. In Chinese philosophy they are characterized by Yin and its associations of the feminine, soft, yielding, diffuse, cold, passive, water, earth, the moon, slowness, and nighttime. Yang, by contrast, is characterized by associations of masculine, hard, solid, focused, hardness hot, dry, aggressive, fire, sky, the sun, and daytime. Jung explains further that-

'Opposed to the guiding principle of life that strives towards superhuman, shining heights, the yang principle, is the dark, feminine, earthbound yin, whose emotionality and instinctuality reach back into the depths of time and down into the labyrinth of the physiological continuum. No doubt these are purely intuitive ideas, but one can hardly dispense with them if one is trying to understand the nature of the human psyche. The Chinese could not do without them because, as the history of Chinese philosophy shows, they never strayed so far from the central psychic facts as to lose themselves in a one-sided over-development and over-evaluation of a single psychic function. They never failed to acknowledge the paradoxicality and polarity of all life. The opposites always balanced one another - a sign of high culture'. [12]

Although little recognised until modern times, Browne’s diptych discourses of 1658 utilize the basic space-time continuum of alchemical mandala art in their respective framework. Urn-Burial thematically concerning itself with Time, while its counterpart The Garden of Cyrus ranges throughout Space for evidence of the Quincunx pattern. Both Discourses are saturated with one of the most common forms of spiritual symbolism, found in Chinese classical literature, Gnostic Medieval alchemical texts and Christianity, symbolism involving Darkness and Light. Together the synergy of Browne's twin Discourses works on a profound associative level, often unconsciously to their reader, as they engage in the fundamental goal of alchemy, the uniting of the opposites.

The dark, corporeal, sublunary doubts, gloom and speculations upon the after-life in Urn-Burial - lost in the uncomfortable night of nothing the alchemical Nigredo of the opus - are intrinsically compatible to the Chinese Taoist concept of Yin. In perfect harmony and equilibrium The Garden of Cyrus concerns itself with Light, the delightful, and the discernment of scientific certainties through occular observation. The Discourse is saturated with symbolism involving Light and Optics and harmoniously represents the Yang half of the literary diptych. Even in terms of the respective music of their prose, the slow, solemn, stately yin rhythms of Urn-Burial are answered by the fast, hasty, Yang prose of Cyrus. Incidentally, it was Browne who coined the very word 'polarity’ into the English language.

Because the psyche at its deepest and most archaic level shares the same symbols which pre-date particular civilizations or cultures, the Chinese Taoist philosophy of Yin and Yang can equally be discerned in the marble sculpture of the alchemical mandala of the Layer monument. Located in the church of Saint John the Baptist at Maddermarket, Norwich, the right-hand pilaster of Christopher Layer's monument depicts sub-lunar suffering, the earth and the feminine, corresponding to the principle of Yin while its left-hand pilaster with its depiction of masculine genitals, vigour, playfulness and victoriousness corresponds perfectly to the principle of Yang.

Richard Wilhelm's translation of The Golden Flower includes an image of a Chinese adept in contemplation of 'inner heaven'. It may well have appealed to Browne's predilection for the number five and its variants (image below). One can't help also wondering that had Browne ever viewed the modern-day national flag of China with its 4+1 symbolism of 5 stars, each of which is five-pointed, he may have included mention of it in his discourse as yet more visible evidence of the archetypal pattern of five.

Jung reminds his reader that Chinese alchemy is structured upon five elements, identifies the alchemical theme of The Garden of Cyrus and obliquely links Browne's quintessentially hermetic essay to Chinese alchemy, stating -

'the quinarius or Quinio (in the form of 4 + 1 i.e. Quincunx) does occur as a symbol of wholeness ( in China and occasionally in alchemy) but relatively rarely’. [13]

Astoundingly Junn stated of the Quincunx pattern itself-

This is a symbol of the quinta essentia, which is identical with the Philosopher’s Stone. It is the circle divided into four with the centre, or the divinity expressed in four directions, or the four functions of consciousness with their unitary substrate, the self. [14]

In modern times Edward W. Said's seminal study

Orientalism (1978) explores Western perceptions of the East in the arts. Chinese influences upon Western painting, the development of stereotypes, and the reinforcing of Western cultural and intellectual prejudices are examined in Said's ground-breaking foundation work of Oriental studies. Crucial to Oriental studies since William Said's publication, is the understanding, for example, that the philosopher Zhuang Zhou (circa 325 BCE), a contemporary of Plato, is not inferior, less profound or weaker as a philosopher than the 'father of Western philosophy'. It is simply that the two philosophers fundamentally differ in their philosophical focus, Zhuang-Zhou is more concerned with individual ethics and personal morality than the cosmic and metaphysical speculations of Plato.

Sir Thomas Browne is the very earliest English philosopher to be interested in China and only one of many writers, painters and composers who have shaped Western perceptions of the Near and Far East, for good and bad over centuries. Incidentally, another early Norwich-Chinese cultural connection exists through the founding father of ballet and dancing-master Jean-Georges Noverre (1727-1810). Noverre occasionally resided in Norwich. Seeing the English and French craze for

Chinoiserie he choreographed his very first ballet

Les Fetes Chinoise (1754) with music by Rameau, with a Chinese theme.

* * *

The English journalist, novelist and poet William Dunkerley (1852-1941) penned the lines of the famous hymn which begins -

In Christ there is no East or West. Dunkerley was inspired by Christ's prophecy in the Gospel of Matthew in which Jesus declares-

I tell you many will come from the East and the West, and shall sit down with Abraham and Isaac and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven [15]

. Dunkerley's Christian sentiment echoes that of the German polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) a sympathetic ambassador of East-West relations, who declared in his secular verse. [16]

East and West Can no longer be kept apart.

It is this imperative task, as C. G. Jung eighty years ago realised, with China's continuing advance in role upon the world-stage, of developing a greater understanding between Western and Eastern minds, which remains unresolved in the world today.

Notes

[1] P.E. Bk. 2 chapter 5: 7

[2] P.E. Bk. 6 chapter 8

Quinsay now Hang-chou was visited by Marco Polo.

[3] Oedipus Egypticus Rome 1652-56 Catalogue p. 8 no. 90

[4] China illustrata Amsterdam 1667 Catalogue p.8 no. 92

[5] China illustrata p. 140

[6] Miscellaneous Tract 12

[7] Miscellaneous Tract 13

[8] CW 13: 2

[9] CW 13: 84

[10] CW 17: 232

[11] CW 14: 660

[12] CW 13: 7

[13] CW 18: 1602

[14] CW 10: 737

[15] Matthew 8. v. 11

[16] In Original- Orient und Occident/Sind nicht mehr zu trennen

Essay dedication - to Yafang for inspiration AND, to Carl for his birthday and return from China.

Bibliography

* Athanasius Kircher - A Renaissance Man and the Quest for Lost Knowledge

Joscelyn Godwin London 1979 Thames and Hudson

* Athanasius Kircher - The Last Man Who Knew Everything

ed. Paula Findlen RKP 2004

* Richard Wilhelm/C.G.Jung - The Secret of the Golden Flower RKP 1931

* 1711 Sales Catalogue of Thomas Browne and his son Edward's libraries ed. J.S.Finch pub. E.J.Brill 1986

.jpg)